StudySmarter - The all-in-one study app.

4.8 • +11k Ratings

More than 3 Million Downloads

Free

Americas

Europe

The French Revolution was a watershed moment in European history. It saw the shocking execution of a King at the hands of the people. It dethroned the Church from its sacred position and, to the shock of a whole continent, denounced Christianity itself. It even changed the very fabric of time, implementing a Revolutionary calendar and time system. 200 years later, the French Revolution is as controversial as ever.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenThe French Revolution was a watershed moment in European history. It saw the shocking execution of a King at the hands of the people. It dethroned the Church from its sacred position and, to the shock of a whole continent, denounced Christianity itself. It even changed the very fabric of time, implementing a Revolutionary calendar and time system. 200 years later, the French Revolution is as controversial as ever.

The French Revolution can be divided into six stages, starting from the origins of 1789 to Napoleon's rise to power.

| Date | Period |

| c.1750–89 | Origins of the French Revolution. |

| 1789 | Revolution of 1789. |

| 1791–92 | Constitutional Monarchy. |

| 1793–94 | The Terror. |

| 1795–99 | The Directory. |

| 1799 | Napoleon seized power. |

When the French Revolution erupted, it was a shock to the French monarchy. But the problems leading up to the Revolution had existed for decades and, in some cases, centuries.

The structure of French society in the 1700s was feudal. In the French case, this meant that society was strictly divided into three classes or Estates:

Estate | Population % | Description |

First | 0.5 | The bishops and priests of the Catholic Church. |

Second | 1.5 | The nobility. This included extremely rich and extremely poor nobles. |

Third | 98 | The commoners. This was made up of wealthy merchants at the top and poor urban workers at the bottom. In the middle were peasants who made up to 85% of the estate. Despite being the poorest estate, the Third Estate was the most heavily taxed. |

French involvement in costly international wars had left it flooded with debt. This financial crisis would hit the Third Estate the hardest and, coupled with the high taxes they faced, made the Third Estate a source of dissatisfaction and riot.

But the King of France was seen as God's representative on earth. Even a century earlier, protesting against the King would have been unthinkable. What happened in the 1700s to change that?

The Enlightenment can be credited for introducing and popularising new ideas of government. The Enlightenment was an intellectual movement whose philosophes saw themselves as the height of reason and science.

Philosophes: French thinkers and writers who believed in the superiority of human reason. Famous examples include Voltaire and Rousseau.

These are some values of Enlightenment thinkers:

Against | For |

Superstition. | Reason. |

All the power is in the hands of the monarchy. | Checks and balances against the monarchy, like in Britain. |

Corruptions of the Church, e.g. excessive wealth and land ownership, tax exemptions, and debauchery of the clergy. | A Church is free of corruption and accountable to its believers. |

In the years leading up to 1789, the monarchy faced crisis after crisis. Most pressing was the fiscal crisis. By 1786 the treasury had a deficit or shortage of 112 million livres. It was the Crown's attempts to avoid going bankrupt that led to the outbreak of the Revolution.

What is a revolution?

A revolution is the forceful overthrow of the ruling power.

In the French Revolution, these forceful transfers of power occurred countless times. It is easier to understand the French Revolution as a series of multiple revolutions, all responding to each other.

The King, Louis XVI, hoped to get the country out of debt through economic reforms. His minister for finance, Calonne, developed a reform package including taxing the powerful First (Church) and Second (nobility) Estates. But to Calonne's frustration, his reforms were met with opposition from three groups, legal and political:

| Group | Description | Reason for opposition |

| Parlements | The high courts. | They argued these tax reforms were too large and sudden for them to implement. It did not help that they were run entirely by the nobility. That is the very people the monarchy was hoping to tax. |

| The Assembly of Notables | A group was created to give their approval to Louis XVI and Calonne's reforms. It was made up of powerful judges, nobles, and bishops. | They argued that they were not a legitimate public body. Instead, they said that the Estates-General were the only body with the power to approve taxation. |

| Estates-General | An old assembly that had not been called since 1614. It was made up of representatives of the Three Estates. | Louis XVI declared that the assembly would vote by order and not by individuals. This meant that if the First and Second Estate voted together, they could always out-vote the much larger Third Estate. The Third Estate refused to work in the Estates-General. When they declared themselves the National Assembly and swore they would make a truly representative constitution for the nation, the French Revolution had begun. |

Did you know? Writer and intellectual Abbe Seyes’ wrote the political pamphlet ‘What is the Third Estate?’ in 1789. This was a radical text because it suggested that the Third Estate should be of equal importance to the other two Estates.

The French Revolution in 1789 was a chaotic period of political protest and food riots. The nation's debt crisis coincided with freak weather, creating poor harvests and mass unemployment. The price of bread almost doubled in Paris. 1789 saw violence and unrest from many groups in the Third Estate: urban workers, market women, and the peasantry.

The Storming of the Bastille was one of the most symbolic events of the Revolution. Political pamphleteers had followed the Estates-General closely and reported the King's actions directly to the Parisian public. When Louis XVI attempted to suppress the National Assembly, Parisians rose up in opposition.

When describing the Storming of the Bastille, historian William Sewell Jr said that it was:

[An expression of] popular sovereignty and national will.1

Urban workers targeted the Bastille, a royal prison symbolising the ancien régime. They liberated the prisoners, some of whom had not seen daylight for decades. As Sewell Jr commented, the storming of the Bastille represented the people's desire for genuine political reform.

Ancien régime: meaning the 'old' regime. This was used to refer to the structure of France prior to 1789, especially the Estates system and the total power held by the King.

The representatives of the Third Estate had broken off from the Estates-General and declared themselves the National Assembly. They named themselves this to emphasise that they represented the nation's interests, not the King's. With the support of Paris, the new National Assembly set out its principles on paper.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was drafted in August 1789 by Marquis Lafayette, a French aristocrat and National Assembly member. Lafayette fought in the American Revolution and his friend Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration of Independence, helped draft this Declaration.

Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.2

The Declaration set out that everyone was equal under the law. It is important to note that 'everyone' meant men - and only men with property.

The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.3

The National Assembly argued that their aim was to preserve the rights of man which they defined as liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

The summer of 1789 was not just notable for political developments in the National Assembly. As France experienced one of its worst-ever food crises, peasant riots erupted across the country.

The role of rumours was important in the Great Fear. Across the country rumours circulated of armed vagrants stealing what was left of the grain supply or of the King seeking revenge on those who supported the National Assembly. Peasants armed themselves preparing for a confrontation. Some looted and burnt down the manors of their aristocratic lords. Others ripped up their seigneurial contracts.

Seigneurialism was the land system in France. Peasants farmed the land for their seigneur (lord) and owed him cash, produce, or labour.

The seigneur was allowed to demand unpaid labour from his peasants. This was called the corvee. The corvee was deeply unpopular amongst the peasantry. If peasants tried to resist, they were tried in seigneurial courts, where their lord was the judge.

The National Assembly saw the great depth of peasant resentment against the aristocracy. They hoped to end the unrest by abolishing the seigneurial system in their August Decree (1789). This helped to end peasant violence but provoked much concern from the nobility.

In October 1789, a mob of Parisian market women marched out of the city and to the Palace of Versailles, the home of Louis XVI. The worsening bread crisis pushed the market women to the edge. They demanded that Louis XVI came back to Paris to sort out the food crisis.

Fig. 1 - Drawing of women marching to Versailles, 5 October 1789.

Fig. 1 - Drawing of women marching to Versailles, 5 October 1789.

Thus, on 6 October 1789, the mob forced and escorted the royal family back to Paris. Louis XVI was now essentially a prisoner to the people of Paris.

The National Assembly set forth to create a constitutional monarchy to solve France's problems. They set about reforming the nation's complex administration and bureaucracy. They even created a revolutionary calendar and decimalised time into units of ten.

The National Assembly modelled their constitution after America's. They changed their name to the National Constituent Assembly to reflect this purpose. They agreed that France would be a constitutional monarchy with a legislative or law-making body. Only 'active' or tax-paying citizens could be allowed to vote.

Did you know?

The Constitution retitled Louis XVI from 'King of France' to 'King of the French' to reflect that his power stemmed directly from the people.

Two factions emerged in the National Assembly: the Jacobins (left-wing revolutionaries) and the Feuillants (monarchists and reactionaries). However, before the constitutional monarchy could properly get underway, events unfolded to generate deep distrust and suspicion of Louis XVI.

Despite Louis XVI seemingly agreeing with the Constitution, he attempted to flee from the Revolutionaries. On 20 June 1791, he and his family disguised themselves and tried to cross the French border into the Austrian-ruled Netherlands. Before they could reach their destination, they were caught in Varennes and humiliatingly marched back to Paris. As historian William Doyle puts it:

There had been hardly any republicanism in 1789... [b]ut after Varennes, the mistrust built up by his long record of apparent ambivalence burst out into widespread demands... for the king to be dethroned.4

Louis XVI's flight to Varennes severely damaged faith in the monarchy. The King was now seen as an enemy of the Revolution.

The new constitution created a new political body called the Legislative Assembly which oversaw the country's laws. The Feuillants and the Jacobins clashed heads with each other in the Legislative Assembly. Internal divisions meant that the Jacobins split into two groups: the moderate Girondins and the radical Montagnards. It was the Girondins who began the war against Austria.

Did you know?

The Girondins hoped that a war against Austria would distract the public away from the economic crisis and bolster support for the Revolution.

In April 1792 France declared war on Austria hoping for a quick victory. To their utter horror, they quickly faced loss after loss against the Austrians.

The Austrians continued to win battle after battle. But it was only when they were about to cross the French border that true panic set in. Rumours that Louis XVI was conspiring with the Austrians to bring down the Revolution circulated all around Paris.

On 10 August 1792, urban workers mobbed the King's palace, the Tuileries Palace. The King's troops and guards quickly abandoned Louis XVI. Some fled, hoping to avoid a bloodbath, while others, called the Fédérés, turned against the King and joined the mob.

Fig. 2 - Execution of King Louis XVI

Fig. 2 - Execution of King Louis XVI

The Legislative Assembly recognised that the constitutional monarchy had failed. It abolished the monarchy and dissolved itself, calling for a new Republic to be created. The Legislative Assembly's replacement was the National Convention.

On 21 January 1793, Louis XVI was executed for his crimes against the Revolution. His execution provoked war from an outraged Britain and led to escalated aggression from Austria.

The most enduring image of the French Revolution has been the guillotine. It was the Terror that popularised this association, executing 17,000 people in the course of a year (September 1793 – July 1794). It was the paranoia and fear of war that laid the groundwork for The Terror.

The Committee of Public Safety (CPS) was built as a war council to prevent the tide of Austrian victories. High-ranking generals had defected to the Austrian side, and rumours of French collusion with the enemy ran unchecked throughout the nation.

The war made and broke the Girondin faction. Their previous popularity quickly crumbled as the war turned for the worse. By the summer of 1793, the Girondins were so unpopular that the Montagnards (radical Jacobins) easily pushed them aside and soon executed them. The CPS was now dominated by the Montagnards who quickly established a dictatorship.

As the war raged on, the CPS introduced greater vigilance and harsher punishments for those suspected of being enemies of the state. A civil war erupted in the Vendee which only increased fears of the enemy from within.

Why did civil war erupt in the Vendee?

The Vendee was a rural area in western France. It was deeply religious and devoted to the King.

The Revolution's attacks on the Catholic Church, the execution of Louis XVI, and the introduction of military conscription pushed the Vendee towards a Counter-Revolution.

In April 1793 the Catholic and Royal army was formed in the Vendee to oppose the Revolution. It was mainly made up of peasants and farmers. They used the motto Dieu et Roi ('God and King').

The revolutionary army was brutal to the Vendeans, burning down farmland and shooting and killing civilians. The Vendee's Counter-Revolution was crushed and defeated by the end of 1793.

One of the Terror's most important laws was the Law of 22 Prairial, with Prairial being June in the French Revolutionary calendar. It bolstered the power of revolutionary tribunals, or law courts, to act without impunity. It forced tribunals to acquit suspects or sentence them to death. No longer could fines, imprisonment, or parole be used as alternatives. The number of executions shot up in June 1794.

Maximilien Robespierre was the most significant leader of the Terror. He was a leader of the Montagnards and was popular with the radical urban workers of Paris.

Fig. 3 - Drawing of Maximilien Robespierre c. 1792.

Fig. 3 - Drawing of Maximilien Robespierre c. 1792.When Robespierre was elected to the Committee of Public Safety (CPS), he helped bring the Terror to reality. He and the other Committee leaders pushed through laws that suspended individual rights and used the Terror to get rid of their rivals. He even imposed a new religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being, with himself as the leader.

His actions led to fears that no one was safe from Robespierre's purges. His opponents in the CPS assassinated Robespierre in July 1794.

Dissatisfaction with Robespierre and the Terror led to a counter-revolution in the government. Conservatives and liberals allied to oust the radical Jacobins from power. They hoped to restore the Revolution to the original values (liberty and freedom) of 1789. This group was called the Thermidorians.

The Thermidorians were a political group in the National Convention that was committed to free trade. Their rise to power was called the Thermidorian Reaction. Though they hoped to end the Terror, they soon resorted to its techniques to purge the Convention of their opponents, the Jacobins.

Free trade: the trading of goods without restrictions or limits imposed by the government.

The Thermidorians removed price controls from food and goods which led to the skyrocketing of prices. 1795 was marked by mass starvation and riots in the cities. The Thermidorians were fearful of a resurgence of both the left-wing Jacobins and the right-wing royalists. They hoped by establishing a new constitution they could stabilise France once and for all. Their hopes came in the form of the Directory.

The Directory was an executive committee made up of five men appointed by the National Convention. The committee was a deeply controversial group and faced resistance from royalists on the right and Jacobins on the left. The Directory was forced to look towards the military for support: it was the army under Napoleon Bonaparte, a young and promising general, that helped maintain the peace.

FIg. 4 - Portrait of Napoleon

FIg. 4 - Portrait of Napoleon

But this solution would later turn out to be the Directory's biggest problem. Lacking good leadership and facing opposition from all sides, the Directory heavily relied on Napoleon's army to remain in power. That made the Directory extremely vulnerable to Napoleon. Indeed, when Napoleon staged a coup d'etat and established himself as leader of the nation in 1799, the Directory was powerless to stop him. Napoleon's rise to power signalled the end of the French Revolution.

Coup d'etat: a sudden and violent seizure of power from a government.

By 1799 it became clear that the Revolution had failed. Napoleon had seized power and in 1802 declared himself leader for life. Despite this failure, the Revolution certainly had long-lasting effects on France.

| Effect | Description |

| End of the Bourbon dynasty. | The execution of Louis XVI signalled the end of the Bourbons. Although the Bourbons were restored to the throne in 1815, this only lasted for 15 years before they were once again overthrown. |

| End of seigneurialism. | Peasants were no longer subjected to the exploitation and taxes of their lords. |

| Change in land ownership. | The Revolution broke up the chokehold the Church and nobility had on land in France. Peasants gained their own land. |

| Reduction of power of the Church. | The French Revolution had attacked the Church and its wealth and confiscated its land and goods. It even disclaimed Christianity. Although Napoleon restored some of the Church's powers, the Church would never be as influential, wealthy, and popular as it was before the Revolution. |

| Popularisation of republicanism. | The Revolution had challenged the divine right of kings or the idea that the King was God's representative on earth. It showed that alternative governments, without a monarchy, were possible. |

The French Revolution is seen as a transformative moment toward modernity. It ushered in what the famous Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm called:

The age of Revolution.5

The most immediate revolution was the Haitian Revolution beginning in 1791 when Haitian slaves revolted against France for their freedom. The enslaved Haitians forced the French revolutionaries to consider how far their ideals of 'liberty' and 'freedom' actually went. The Haitian Revolution was the first and only successful slave revolution in the modern world.

In 1848, revolutions across Europe, including the German states, the Italian states, and Austria, erupted, partly inspired by the French Revolution.

The French revolution began in 1789. A key date was 20 June 1789 when the Third Estate pledged to give the nation a constitution.

The French Revolution was a series of revolutions beginning in 1789 and ending with Napoleon's rise to power in 1799.

The French revolution started in 1789 but the exact date depends on your definition of revolution. The Estates General met on 5 May but largely as subject to the King's wishes.

A more important date was 20 June, when the Third Estate broke off from the Estates General and opposed the King. They swore they would give the nation a constitution.

Long term causes:

Short term causes:

The Revolution ended in 1799 with Napoleon's rise to power. This is because Napoleon was firmly against the Revolution and its values.

Flashcards in The French Revolution289

Start learningWhat year did the French Revolution begin?

1789

True or False: The French social system comprised of 5 Estates

True

What Assembly was formed after the last meeting of the Estates-General in 1789?

French Assembly

True or False: The attack on Bastille was to diminish any symbolism of the King’s rule

True

What country did France declare war on in 1792?

Britain

True or False: The Reign of Terror was an event to eliminate all those who were threats to the King

True

Already have an account? Log in

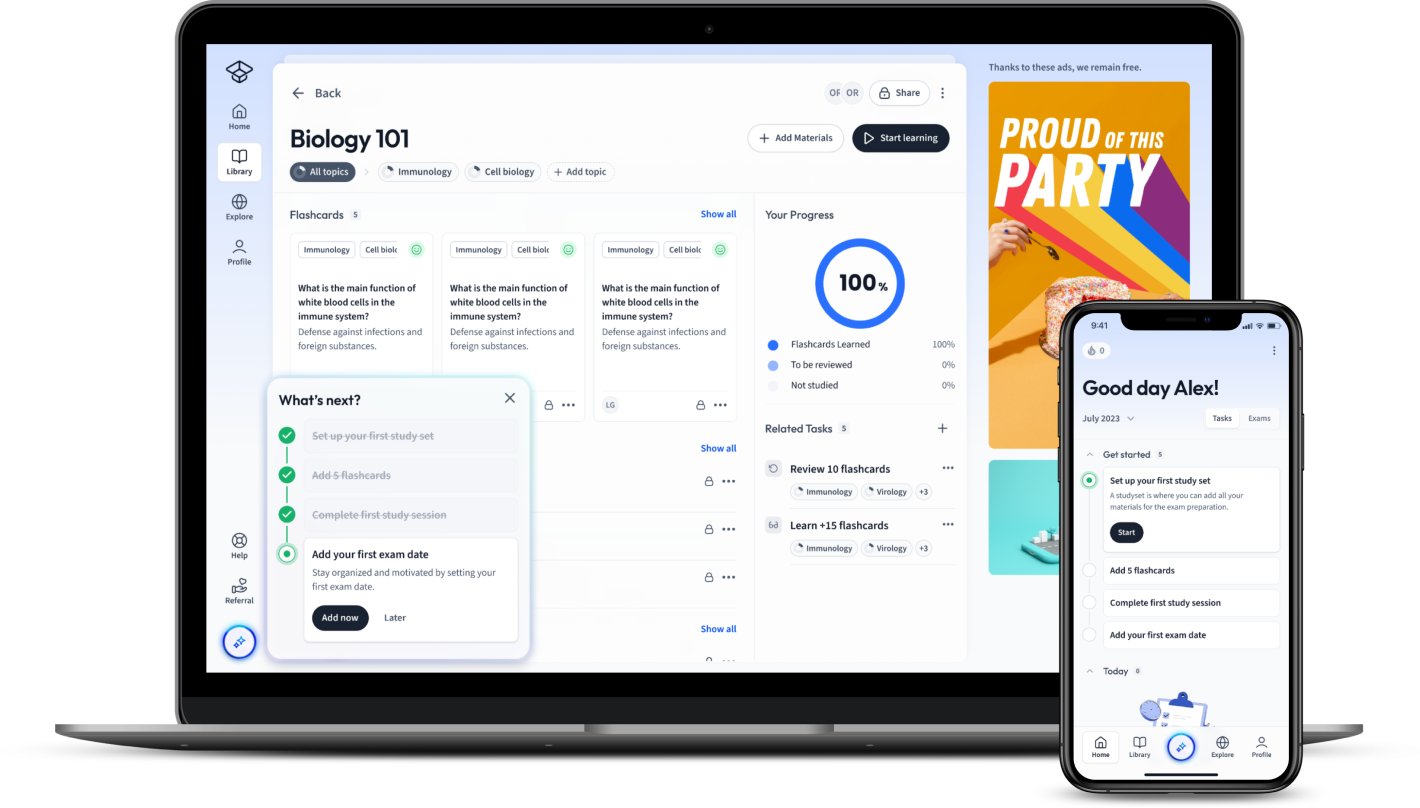

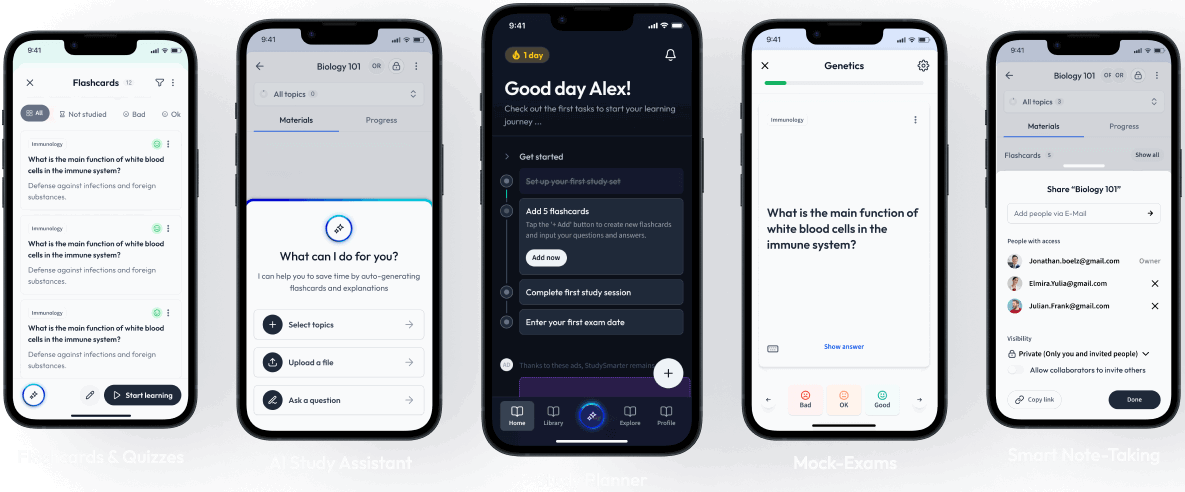

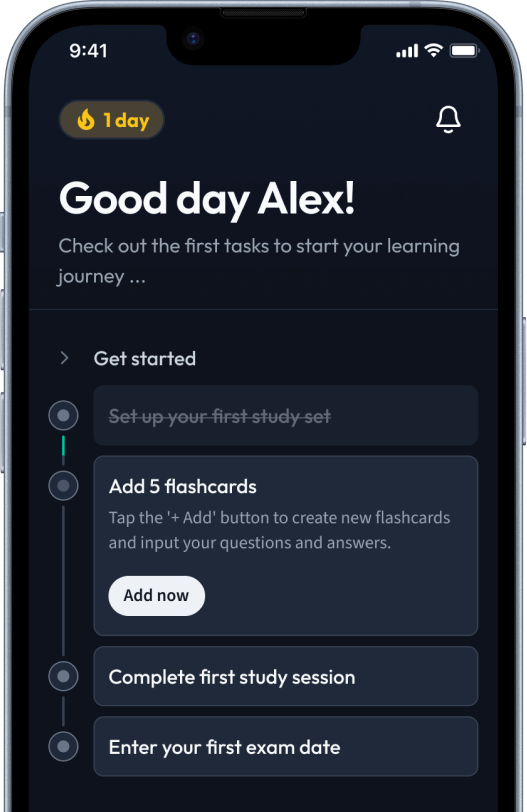

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in