StudySmarter - The all-in-one study app.

4.8 • +11k Ratings

More than 3 Million Downloads

Free

Americas

Europe

How can one religious movement be responsible for shaping modern society as we know it? Nation states, freedom of information, freedom of religion, and the toppling of the Catholic stronghold over Europe – all of these can be seen as a result of Martin Luther's accomplishments with the Protestant Reformation. So, what was the Protestant Reformation, and how did it change the world? Luckily, you're about to find out – hallelujah!

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenHow can one religious movement be responsible for shaping modern society as we know it? Nation states, freedom of information, freedom of religion, and the toppling of the Catholic stronghold over Europe – all of these can be seen as a result of Martin Luther's accomplishments with the Protestant Reformation. So, what was the Protestant Reformation, and how did it change the world? Luckily, you're about to find out – hallelujah!

Let's look at a timeline of the history of the Protestant Reformation.

| Date | Event |

| 1517 | Martin Luther published his 95 Theses on the Wittenberg All Saint's Church door, kicking off the Protestant Reformation. |

| 1519 | Zwingli preached the Reformed Doctrine in Zurich, Switzerland. King Charles V became the Holy Roman Emperor. |

| 1522 | Anabaptism was founded following Zwingli's call for reform. |

| 1524-5 | German Peasants War. |

| 1536 | King Henry VIII created the Church of England after he renounced Roman Catholicism in 1534. |

| 1541 | After the death of Zwingli in 1531, the Swiss Reformation lacked a leader. John Calvin was invited to Geneva to lead, and a power struggle followed. |

| 1545 | The Council of Trent embodied the beginning of the Catholic Counter Reformation. The Council existed until 1563. |

| 1546-7 | Schmalkaldic War. |

| 1555 | The Peace of Augsburg allowed the legal split of Christianity into Catholicism and Lutheranism.John Calvin became the official leader of the Swiss Protestant Reformation. |

| 1558 | Ferdinand I succeeded Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor. |

| 1618-48 | The Thirty Years' War. |

| 1648 | The Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years War and established state sovereignty throughout Europe. The Holy Roman Emperor no longer held Catholic control of the European continent. |

Catholicism is the oldest form of Christianity. The Catholic Church's first pope was St Peter, one of Jesus' twelve disciples. However, this did not mean that Catholicism went unchallenged. Across Europe, divides would emerge within the Church.

Did you know? To this day, the pope resides in the Vatican City, which is the smallest state in Europe! The City is a small neighbourhood in Rome, Italy, that is independent from the Italian state.

In 1054, the Catholic Church broke into two. Its eastern half formed the Eastern Orthodox Church which was dominant in eastern and south-east Europe, especially in Greece.

The next large split was the Protestant Reformation, which began in 1517. While the split in 1054 saw south-eastern Europe break off from the Church, the Protestant Reformation represented the break up of western Europe from within.

The Protestant Reformation, beginning in 1517, was ushered in by the German priest Martin Luther. He criticised the corruption of the pope and called for a return to the words of the Bible. This protest became known as Protestantism, which became a flashpoint for religious wars, peasant uprisings, and other reform movements, such as the Swiss Reformation.

However, Martin Luther was not the first in western Europe to protest against the Catholic Church. The English reformer John Wycliffe was notable for translating the Bible into English in 1380, protesting against the Church's Latin-only Bibles. The Czech religious philosopher and writer Jan Hus also led a reformation movement in 1402 throughout what is now the Czech Republic.

Both reformers protested the Catholic Church's corruption and inability to maintain unity across Europe, which was made clear in the Western Schism (1378 - 1417). Confusion and controversy over who would become the next pope led to 3 different popes and their power bases existing at the same time! This situation lasted for 40 years, showing the Church's weaknesses and fragility. However, despite these internal conflicts, the Catholic Church suppressed Wycliffe and Hus and squashed their radical ideas.

Fig. 1 Sketch of the Gutenberg Printing Press, invented in 1450.

Fig. 1 Sketch of the Gutenberg Printing Press, invented in 1450.

So why did Martin Luther succeed when John Wycliffe and Jan Hus had failed? Luther even drew on the ideas of Wycliff and Hus in his religious reform, so you might expect Luther to have faced a similar fate.

It was the invention of the Gutenberg Printing Press (1450) that helped make Luther's movement a success. The press made printing new ideas quicker and cheaper, allowing Luther's ideas to reach many audiences. This made it difficult for the Catholic Church to suppress as it had previously done.

The long and often violent battle for religious reform in western Europe began with Martin Luther. His proposals about defying the pope and returning to the Bible spread throughout Europe, instigating other Reformation movements. Most notable of these was Calvinism which emerged in Switzerland. Let's look at how Luther and Calvin became the driving forces for the Protestant Reformation throughout the 16th century.

When Luther wrote his 95 Theses in 1517, he was intending to open a discussion about the Catholic Church's practices. His key points of contention were the Church's sale of indulgences and the traditional power of the pope over the scriptural power of the Bible.

He professed three beliefs as the heart of Christianity: sola scriptura (only by the script, i.e. the Bible), sola fide (only by faith), sola gratia (only by grace). These three beliefs meant that holy scriptures (such as the Bible) were the highest form of authority, and that Christians could reach salvation, not through indulgences, but through faith alone. This faith was transformed into salvation through the grace of God.

What were indulgences?

Indulgences were originally acts of worship carried out to be excused for an act of sin. In the 11th and 12th centuries, indulgences often took the form of participating in the Reconquista period or The Crusades on behalf of the Church.

As Catholic theory developed, indulgences were defined as acts of “good work.” These acts ranged from pilgrimages to holy sites like Jerusalem or donations to Church buildings to help spread the faith. These acts of good work would lessen a Christian's time in purgatory, the mid-way stage between heaven and hell.

The Church developed a system of “commutation” where these acts of good work could be converted into a monetary value. Commutation led to an abuse of the indulgence system, and getting into heaven became a monetary transaction rather than an act of faith. It was this corruption within the Catholic Church that Luther and other reformers were looking to change.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, the pope's power weakened as monarchies grew stronger across Europe. The Western Schism (1378 - 1417) was particularly damaging for the Church's reputation and demonstrated the fracturing of Catholic religious control over Europe. Criticism against the pope grew,

Luther's religious ideas became known as Lutheranism and emerged in Wittenberg, in northern Germany. Some of the regional German rulers, called princes, converted to Lutheranism. For the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, who ruled over these princes, Protestantism represented a threat to his great Catholic empire. Indeed, many of the princes converted precisely because Luther's ideas defied the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Fig. 2 Martin Luther, leader of the Protestant Reformation.

Fig. 2 Martin Luther, leader of the Protestant Reformation.

War soon broke out between Charles V and the German princes, called the Schmalkaldic Wars. After 10 years of sporadic fighting, a peace treaty was signed. The 1555 Peace of Augsburg granted Lutheranism a legal status and created the policy of cuius regio, eius religio (whose realm, their religion). Princes could choose their locality's religion within the Holy Roman Empire, to be either Catholic or Lutheran.

Did you know? The name 'Protestants' originated in 1529. The German princes protested against Charles V's punishment of Luther and anyone who followed him. This event was called the Protestation at Speyer.

Luther died the year after the Peace of Augsburg, in 1556, having achieved the legitimacy of Lutheranism. However, other denominations had formed elsewhere in Europe, such as Calvinism in Switzerland, and did not have this status. Hence, the Protestant Reformation continued whilst Calvin's followers fought for the same position as Lutherans.

The Swiss Reformation movement began in the 1520s, with the priest Huldrych Zwingli. Inspired by Luther, Zwingli preached reforms similar to Luther and published his doctrine in 1523. When Zwingli died in 1531, there was a vacancy for the leaders of the Swiss Reformation.

In 1541, the French reformer John Calvin was invited to help develop the Protestant movement in Geneva and after a power struggle assumed leadership in 1555.

Fig. 3 John Calvin, leader of the Swiss Reformation.

Fig. 3 John Calvin, leader of the Swiss Reformation.

Although Calvin died in 1564, he corresponded with many leaders in Europe and created a powerful movement based on his beliefs known as Calvinism. The Peace of Augsburg did not recognise Calvinism, and so the Holy Roman Empire still persecuted his followers. Calvinism spread much further than Lutheranism, reaching England, France, and the Netherlands. English Puritans and Pilgrims spread Calvinism across the Atlantic to the colonies they established in North America.

The Thirty Years' War began in 1618 and saw conflicts arise for countries' territorial ambitions, but also for their respective Christian denominations: Catholicism, Calvinism and Lutheranism. Europe underwent one of its worst conflicts, with nearly half a million dying in battle and a further 8 million from famine and displacement. The Peace of Westphalia (1648) officially recognised Calvinism as a denomination, “ending” the Protestant Reformation after over 100 years of conflict.

Why were Protestants unable to unite as one religious community?

The divisions between Lutherans and Calvinists may make you wonder why Protestantism was so divided, especially compared to the much more unified Roman Catholic Church.

The origins of Protestantism give us a helpful clue. Protestantism emerged as an alternative to Catholicism, which had a hierarchy with the pope and his cardinals at the top. For Protestants, the "priesthood of all believers" doctrine argued that everyone had a direct connection to God, not just priests or the pope. This doctrine opened the floodgates for personal interpretation of the Bible. Luther's ideas soon took a life of their own as different Protestants reached their own conclusions, resulting in branches such as Calvinism.

So, what were the overall changes of the Protestant Reformation? How did it affect European and global history?

Naturally, the Catholic Church was not idle whilst the likes of Luther and Calvin attacked their traditions and beliefs. Pope Paul III revived the Roman Inquisition in 1542 which targeted Protestants, confiscating and destroying any texts that contradicted Catholic beliefs. They also captured Protestants and burnt them at the stake. The Inquisition helped to re-establish Catholic dominance in some countries that had fallen to Protestantism, such as Austria, France, Poland, Italy, Spain, and Belgium.

Fig. 4 Painting of Pope Paul III.

Fig. 4 Painting of Pope Paul III.

Pope Paul III formed the Council of Trent in 1545, which met several times until 1563. The council discussed the growing Protestant Reformation and produced an official Catholic response. The Council laid out a unified, standardised doctrine of Catholic beliefs. It emphasised the power of the pope and offered some reforms of the Church's practices to target corruption.

The Protestant Reformation led to religious wars across central and west Europe. It led to a bloody civil war in France, between Catholics and Huguenots (French Protestants). These wars came to a head with the Thirty Years' War in 1618-48. Although the Peace of Westphalia (1648) saw the end of European religious warfare, religious conflict played out in new lands.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus reached the shores of the 'New World': America. The threat of Protestantism in Europe made the Catholic Church look further afield for new believers. Colonisation by Catholic nations such as Spain and Portugal were characterised by huge conversion efforts, often accompanied by violence and slavery.

What did Protestant religious efforts look like in the New World?

Like Catholics, Protestants brought their religion with them to the New World. However, Protestant colonisation had a fairly different religious character.

Though still accompanied by violence and displacement, Protestant colonies were often closed-off societies and Protestant settlers did not typically believe indigenous peoples worthy of conversion. Protestant settlers like John Winthrop in Massachusetts believed that God had an elect, a chosen few who would be allowed into heaven. He and his fellow English Puritans wished to create a purely religious society that strictly followed the word of the Bible. As such, conversion was not a priority for the English Puritans.

By contrast, Catholic nations such as Spain and Portugal were more restricted by the wishes of the pope. In 1493, the pope issued an order for conversion to be carried out alongside colonisation.

The Protestant Reformation reduced the power of the pope as the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire. Holy Roman Emperor Charles V's successor, Ferdinand I, was the first Emperor not to be crowned by the pope, demonstrating the separation of religion and politics.

The resultant policies from the Reformation, such as the Peace of Westphalia, decreased the power of the Holy Roman Empire significantly and permitted state sovereignty, an early model for nation states. New laws gave Europeans new freedoms of religion and information and created a culture of individual determination.

Fig. 5 Etching by James Barry showing an archangel who demonstrates the nature of the universe to key figures of the Enlightenment. The etching shows the changing role of religion in society during the Scientific Revolution.

Fig. 5 Etching by James Barry showing an archangel who demonstrates the nature of the universe to key figures of the Enlightenment. The etching shows the changing role of religion in society during the Scientific Revolution.

Furthermore, the existence of an alternative Christianity – Protestantism – challenged the Catholic Church's authority over the nature and truth. This ambiguity helped to spur the Scientific Revolution (Enlightenment) during the Reformation, with the likes of Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton developing the scientific method, often against the Catholic Church's religious beliefs.

Over a hundred years of devastating religious warfare led to a reluctant tolerance among European rulers. The Thirty Years War had shown that enforcing religious conformity came at a heavy price. The 1648 Peace of Westphalia was a huge step towards religious tolerance. For the first time, subjects could practice a private religion different from the public religion of their state. This helped to begin the long road towards separation of church and state.

However, it is important to note that these acceptable private faiths were limited to Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. Non-Christian religions such as Judaism were still heavily persecuted. Rather than open tolerance, the Protestant Reformation represented the breakdown of Christian unity in Europe, where religious differences were only tolerated in order to bring an end to war.

In 1962, the American historian G.H. Williams transformed how we understand the Protestant Reformation.1 He argued that there were really two types of Reformations: the magisterial Reformation and the more radical Reformation. Williams' work threw new light onto Reformers outside of Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin. He argued that the Anabaptists represented the radical Reformation.

Who were the Anabaptists?

The Anabaptists were a fringe Protestant group who did not believe in infant baptism. They followed the Bible's words strictly, baptising themselves as adults just as Jesus had done when he was 30 (ana means 'again' in Greek).

The Anabaptists disagreed with Luther's alliance with the German princes. They argued that secular rulers should have no power over the Church. Anabaptists believed the Second Coming of Christ was imminent, and therefore regarded secular institutions (such as princes or councils) as corrupting influences in Christ's dominion.

When Williams identified the Anabaptists as part of the radical Reformation, he meant it in the sense of the Latin word radix. Radix meant to return to the root of something. The Anabaptists were radical because they wished to return to the purely religious community that Jesus had led in the Bible.

In contrast to the radical Anabaptists, Williams coined the term, "the magisterial Reformation". These were Protestant movements that had been backed by local power structures, such as Luther and the German princes or Calvin in Switzerland. Here, the local magistrates helped institutionalise Protestantism into the governing and legal structures. Williams' 1962 work represented a significant break from previous historians, who saw Luther's Reformation as a radical act in of itself, as well as a harbringer of modernity. It would be the magisterial Reformation - backed by the economic, military, and legal power of local rulers - that would reach the greatest success.

The Protestant Reformation was a period of European history that began with Martin Luther's proposals to reform the Catholic Church, known as the 96 Theses. Protestantism was formed as a result, and after over 100 years of inter-denomination conflict between Protestants and Catholics, the Reformation ended with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. This allowed states to decide their religion and saw the breakdown of the Holy Roman Empire's hegemonic Catholic control of most of Europe.

The Protestant Reformation began in 1517 with Martin Luther's publication of his 95 Theses. It "ended" with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

King Henry VIII wanted to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon so that he could have a male heir from a different wife. The Pope refused his request, so Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church and created the Church of England instead.

Whilst previous attempts at reformation had been crushed by the Catholic Church through force and the destruction of heretical documents, Martin Luther was able to use a recent invention. In 1450, Johannes Gutenberg invented the Printing Press, which made mass-production of documents faster. Luther used printing presses to distribute his messages of reformation and form a large following across Europe which the Church could not quash easily.

The effects of the Protestant Reformation are widespread and heavily influenced modern society. Immediately, there was the Catholic Counter Reformation and the decline of the Holy Roman Empire in Europe. The long-term effects include the violence witnessed towards indigenous peoples during colonisation, the creation of nation states, the drive towards secular, scientific knowledge, the separation of religious and political authority and the adoption of democracy across most of Europe.

Flashcards in Protestant Reformation629

Start learningWhen did Martin Luther release his 95 Theses, proposing reformation to the Catholic church?

1517

Which Pope declared Luther's 95 Theses as heresy?

Pope Leo X

What was Luther's main point of contention with the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century?

Indulgences

When was the Diet of Worms?

18th April 1521

At which Diet did Holy Roman Emperor Charles V attempt to unite the religions of his subjects?

Diet of Augsburg

What does the term cuius regio, eius religio mean, the principle decreed in the Peace of Augsburg 1555?

The ruler of a principality would determine its religion

Already have an account? Log in

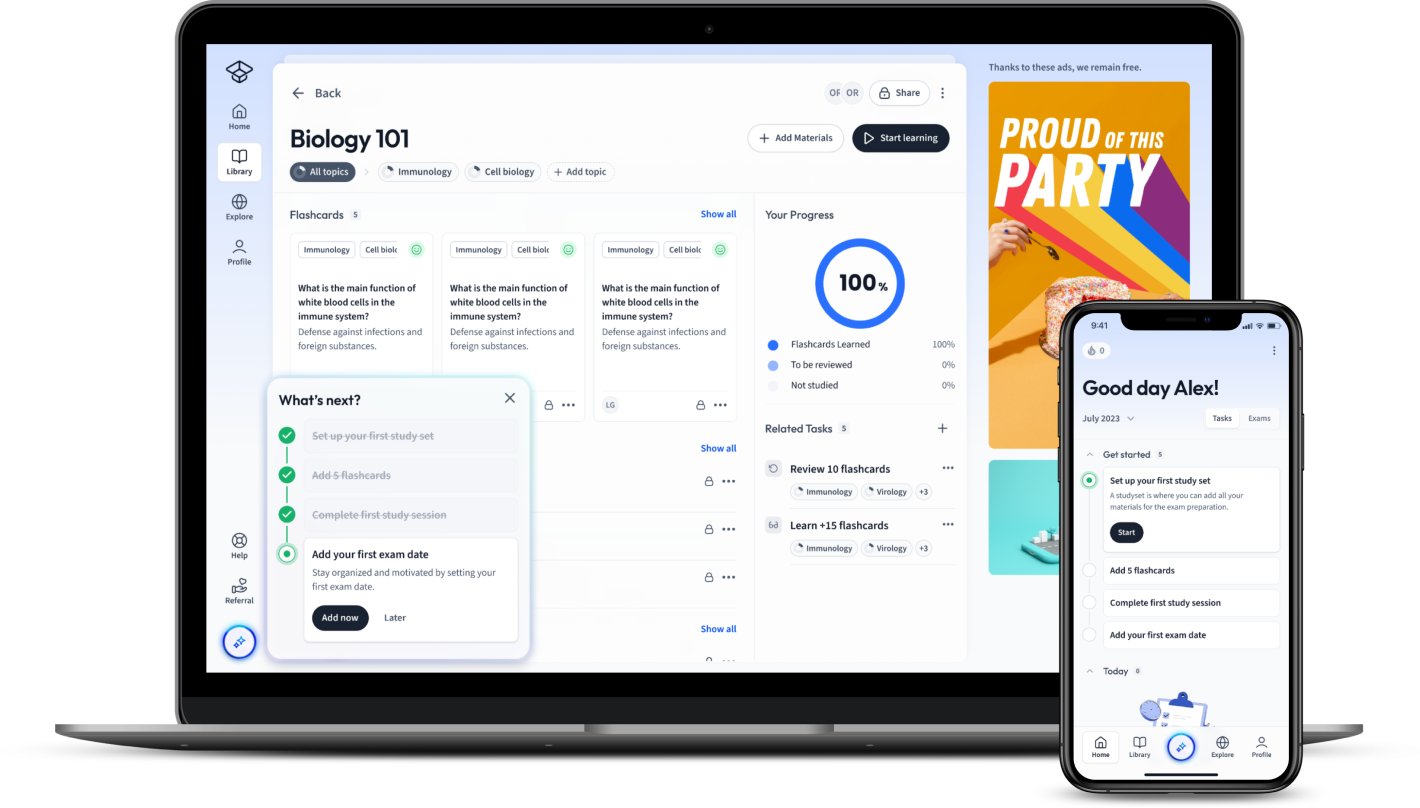

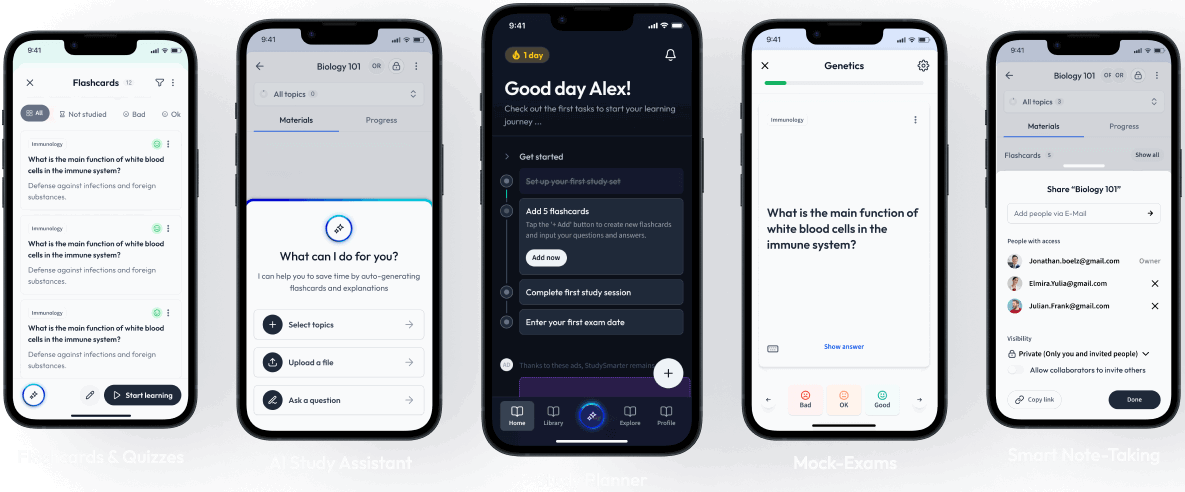

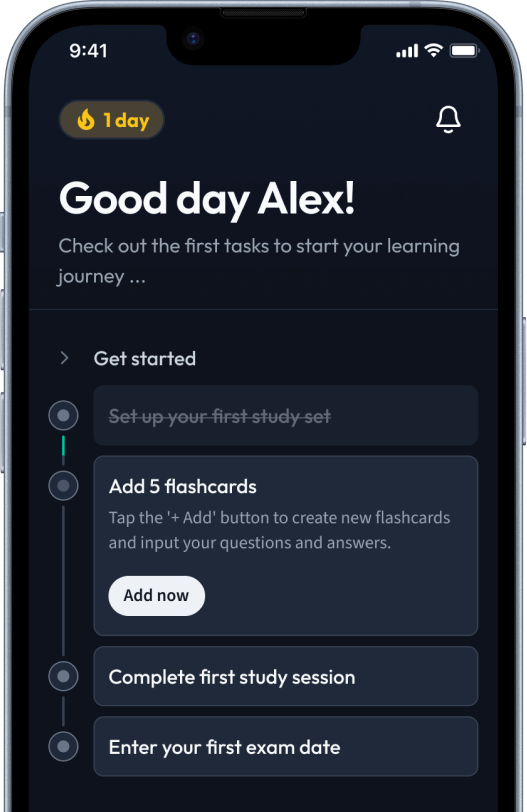

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in